SOLD

Elegant Tsuba by Unno School Master

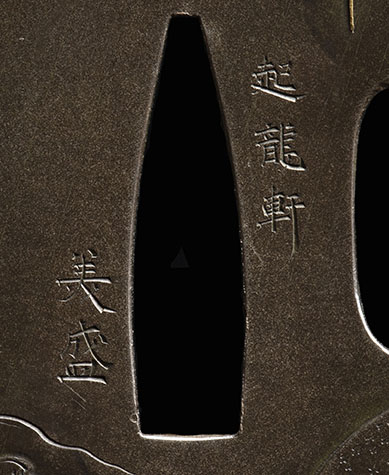

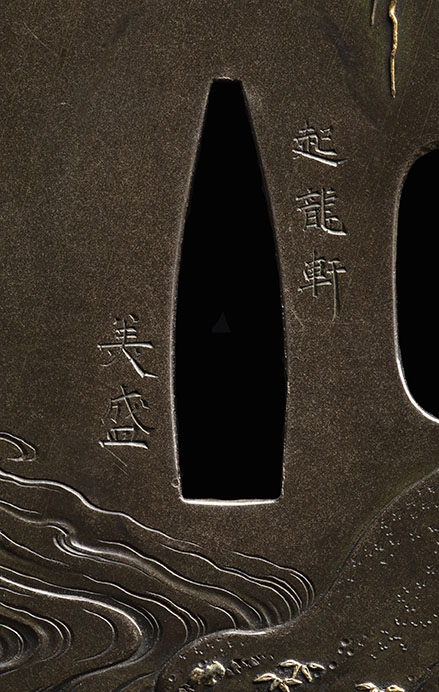

Kiryuken Yoshimori

The Unno school stands in a shining light of magnificence. The masters that emerged from this school were the students and progeny of unquestionably some of the finest and highly regarded artisans not only of their time, but of all time. Their talents adroitly navigated a radically changing art environment due to Japan’s departure of the feudal system, and an increasing fraternization of Western and Eastern cultures due in no small part to the Art Nouveau movement in Europe. A sword craftsman has to diversify into sculpture and jewelry markets to keep the lights on as swords became the symbol of an obsolete time no longer respected or enjoyed. The need for excellent décor for the wealthy foreign aristocrats had eclipsed the needs of the Daimyo, whom as they lost their feudal importance, now were scrambling to segue into new occupations.

Of course, one cannot study the Unno school without paying due attention to the great Unno Shomin. Shomin was born in Mito province in 1844 to Unno Denemon. His first study as a fittings craftsman was with his uncle, Shodai Unno Yoshimori, and he later continued studies in other mediums such as painting and calligraphy. He also studied fittings making with another elite Mito craftsman, the great Hagiya Katsuhira, whom himself was also a student of Shodai Yoshimori. With Japan’s transition out of a fuedal structure with the Meiji Restoration and Hatorei, sword craftsmen were effectively made unemployed. Shomin took on whatever commission was available. He persevered in metal working and changed gears, making sculptures and decorative arts. The sculpture whih is considered to be one of his most significant works, and a sea change in Japanese art was his sculpture of Ranryu-o the Gagoku dancer in 1890 which he entered into the Third National Industrial Exhibition in Tokyo. It won high praise and critical acclaim, launching him into more recognition and successes, and he was appointed a judge for the very same exhibition several years later. He enrolled in the Tokyo School of Fine Arts where he studied under the luminary maker, Kano Natsuo, then became an assistant professor, then professor, and in 1886 he was appointed as an Imperial Household Artist, or “Teishitsu-Gigei’in. This title was the precursor to today’s Living National Treasures. Shomin died in 1915 after struggling with health issues made worse by excessive drinking.

This tsuba was made by the Nidai (second generation) Yoshimori and signed by one of the several different art names he used; Kiryuken Yoshimori. Yoshimori’s birth name was Shinokichi. His father was Unno Moritoshi who was the nephew and student of Shodai Yoshimori. While the second and first generation Yoshimori were related as grand-nephew and uncle respectively, the Shodai had died in 1862 while the nidai was born in 1864. So, use of the same name and kanji was likely by declaration on the part of the nidai. It is recorded that Nidai Yoshimori studied under Shomin, and other significant artists of his time in painting He also became a professor at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and yet another of the Unno line to be appointed an Imperial Household Artist. Yoshimori died at the young age of 56 in 1919.

The design of this tsuba is a parable about a moment in the life of Ono no Michikaze (894-966), also known as Ono no Tofu, one of Japan’s most famous and revered calligraphers. Ono no Michikaze lived and worked in the Heian era (794-1185), and in company with Fujiwara Sukemasa and Fujiwara Yukinari, they are considered the founders of a traditional Japanese calligraphy as a pure Japanese art form. The story opens when Ono no Michikaze is feeling discouraged and unsatisfied with his calligraphy, so he goes for a walk along the bank of a stream. He had been denied promotion at the Imperial Court seven times. He happens upon a frog that is jumping with great effort to reach a hanging willow branch, unsuccessfully. Ono no Michikaze watches as the frog attempts to grab it, jumping over and over again, and thinks to himself how the little frog can’t possibly reach it. At the very moment he is thinking this, a breeze catches the willow and bends the branch down just enough so that on the frog’s eighth attempt, it at last reaches the willow branch and clings to it. Michikaze is astounded and comes to the conclusion that the frog created the opportunity to succeed through shear perseverance. Inspired by the little frog’s determination, Ono no Michikaze set back to his endeavors, accomplishes new heights of calligraphic art, and becomes a legendary figure in Japanese art history.

This story was so popularized in the Edo period that the picture of him, the frog, and the willow are also the subject on a Hanafuda playing card that continues to this day with the scene of Michikaze, a willow tree, and a frog, known as the November “Rain Man” Card. The Japanese government also issued an 80 Yen postage stamp of the story.

In this piece we have a wonderful illustration of the story in magnificent detail, and quality of material and caliber of skill, that is the hallmark of Unno school artisans. The plate is a finely made shibuichi with fine granularity visible in the polished plate. The flowing stream and terrain is superbly carved with soft flowing lines and fine details. Ono no Michikaze, the little frog leaping up, and the willow are inlaid with colorful shakudo, gold, red copper, and silver, in exquisite detail. The detail is quite astonishingly apparent in the care and detail of attention to Michikaze’s clothing, the knots and moss on the willow, the frog, and even the details inside and underneath the parasol Michikaze is carrying. Fine subtle lines representing wind are carved into the plate and a careful look shows that the branches are bending with the wind and the little frog looks just within reach of a one above him as he leaps up.

This tsuba is in excellent condition. The surface of the shibuichi plate does have a few small spots of faint staining that most fittings of copper alloys show. Perfect condition plates with no stains, scratches, or other blemishes are suspect of having been retouched, or restored, and while that is also not in and of itself a diminishing element, with some small blemishes we can say that the plate is likely closer to untouched than retouched. The details are crisply sculpted and the mei is clear and sharp. The nakago ana shows some evidence of having been mounted to a blade, with shadowing on the seppadai from contact with seppa, and small raising on the corners of the nakago ana at the ha. However, the nakago ana itself appears ubu and perhaps it was only mounted upon the blade it was made for from the start. The hitsuana is also unaltered and does not show evidence of having had plugs either installed in the past. It is a superb work by a prominent craftman that exemplifies the Unno school.

It is accompanied by an NBTHK Hozon Tosogu certificate testifying to the authenticity and quality of the piece. It is held in a custom fitted palownia wood box with pillow. A fine addition to any collection.

- Measures: 70.0 mm x 66 mm x 4 mm

SOLD

Legacy Arts has another tsuba with this theme by Shinshinto swordsmith Kaiun Sadayuki. Click here to see it as well.